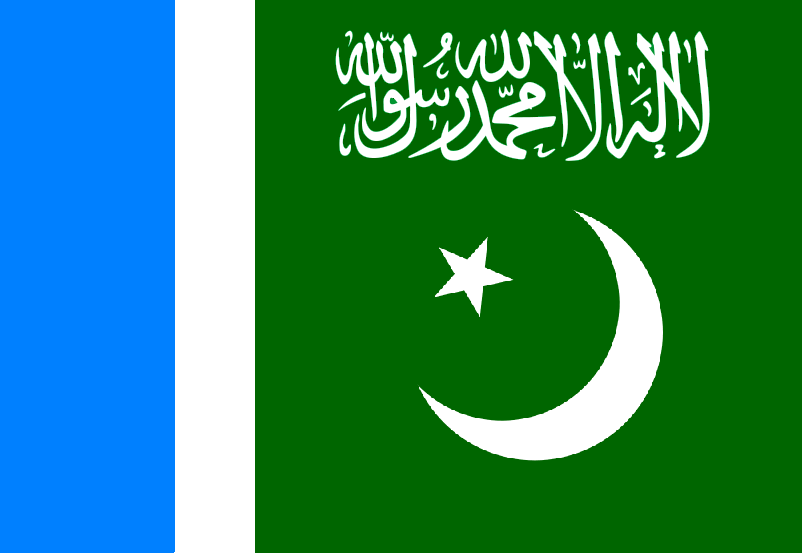

This is a summary of the original paper published by Council on Foreign Relations titled “International Relations of an Islamist Movement“ that may be found here

The author argues that Islamist thinking on international issues stems from a pan-Islamic vision and that the notion of the larger Muslim world plays a central role in it. The universalist claims of revivalism are limited by the reality of the nation-state and Islamist organizations have developed as national political organizations. Universalist rhetoric may serve different purposes and the attitudes of Islamist groups toward international issues are shaped by state policies and the regional and international context. The paper argues that the case of the Jama’at-i Islami can provide valuable insights into the issues raised.

The Jamaat-e-Islami party’s foreign policy was shaped by the legacy of British rule in India and the desire to create a distinct normative order for Muslims. The party was aware of the imperial power structure of the world, but their response was not one of nationalism like Nehru or Gandhi, but rather a desire to preserve their own standards and ideals. The notion of a separate Islamic system was first floated by the religious authorities of the Deoband school and was institutionalized in Muslim religious and political discourse. The ideal of the umma, or Muslim unity, was central to Indian Muslim politics, as historical legacies and institutional contacts with religious centers in Iran, Iraq, and Egypt reinforced the desire to preserve and promote Muslim piety and cultural independence. Mawlana Mawdudi, the party’s chief ideologue and leader, was deeply concerned with the umma, both in creating a pure Islamic order locally and envisioning a universal Islamic order globally.

IDEOLOGICAL ROOTS

Mawlana Mawdudi was an Indian Islamic scholar who was an important figure in the Khilafat Movement in India. He believed that the caliphate was a symbol of Muslim unity and a key institution that would preserve that unity and shape the transnational umma (Muslim community). However, the abolition of the caliphate by the Turkish Republic in 1924 affected Mawlana Mawdudi’s views. He became critical of nationalism, which he viewed as a form of Western domination, and hostile to Arab hostility to Ottoman rule and Turkey’s handling of the caliphate. He also became aware of the growing influence of nationalism on the Muslim imagination and saw the umma as shaping Muslim views on international relations. In terms of the Muslim community in India, Mawlana Mawdudi articulated his views amidst the debate between the Muslim supporters of the Congress Party and those led by Jinnah in the Muslim League. Mawlana Mawdudi was not in favor of secular nationalism, but was not opposed to Pakistan as envisioned by Jinnah. He criticized the anti-imperialism of the Congress Party and was not convinced that it represented Muslim interests. He also had heated debates with senior Indian Islamic leaders who supported the Congress Party and sought to use Islam to mobilize support for the independence movement.

Maulana Mawlana Mawdudi was critical of Western ideologies, viewing the West as an obstructive force seeking to suppress Islam and subjugate Muslims. His opposition to the West was largely rooted in his communalist inclination, where he saw the British colonial rule as responsible for the marginalization of Indian Muslims and the ascendancy of Hindus. However, his anti-Westernism was not the only motivation behind his activism, as he was also concerned with preserving Muslim cultural autonomy. He distinguished between the shortcomings of capitalism and socialism, seeing Islam as a third alternative that embodies the virtues of both systems. In practice, he was more wary of socialism than capitalism, viewing the left as anti-Muslim and closely associated with Indian nationalism. These views would influence the Jama’at-i-Islami party’s foreign policy positions in the future.

The role of Islamic and Islamist concepts was significant in the vision of Mawlana Mawdudi, a Pakistani Islamist thinker. Mawlana Mawdudi was influential in the interpretation of key concepts such as jihad, the Islamic state, Islamic economics, and minority and human rights. He consciously avoided the commonly used caricatures of jihad and instead, interpreted it in a nuanced manner as a properly regulated doctrine of war. Mawlana Mawdudi used jihad as a tool to modernize Islamic perspectives on international affairs and integrated Muslim political life into the international system. He opposed the idea of an undisciplined and militant use of jihad and argued that it could only be declared by a state. He was imprisoned for his views, which were seen as seditious by the Pakistani state.

The Islamic state as conceived by Mawlana Mawdudi is a utopian ideal based on the teachings of the Sharia and the rule of the Prophet and his successors. It represents a modern conception of governance that differs from Western models and is intended to ensure the continuity of the faith and Muslim piety. Mawlana Mawdudi’s views on human rights were developed later in his career, when the Islamic state was criticized for authoritarianism and exclusion of minorities. He argued that non-Muslim minorities would have rights as specified in the Sharia’s teachings on dhimmis and that preserving the purity of the state’s ideology was a foremost concern that justified excluding those not subscribing to its ethos. The debate over human rights in the Islamic state, including women’s rights, has been rekindled in recent years with opposition from feminist movements based on international legal and human rights norms and advocacy by the Jama‘at for a relativity of human rights and better treatment of women in Muslim societies.

FOREIGN POLICY

The Jama‘at’s foreign policy was initially ad hoc and based on the opinions of its leaders, particularly Mawlana Mawdudi. In the 1970s, a younger generation of leaders educated in modern subjects assumed positions of authority, streamlining the Jama‘at’s thinking on foreign policy. The party established an international affairs bureau and research institutes that inform leaders of the Jama‘at’s views. The party also has members and leaders serving in government and parliament, shaping foreign policy. The role of the state and its policies is important in shaping Islamist views on foreign policy, as the state often regulates the party’s international role and encourages its involvement in foreign policy when it aligns with national interests.

Jamaat’s first foreign policy position was regarding the province of Kashmir. The Jamaat believed that the Muslim-majority province should join Pakistan and was willing to go to war with India if necessary to secure it. However, Mawlana Mawdudi’s hawkish stance was met with criticism from the government, which accused him of undermining efforts of volunteers fighting in Kashmir. Since then, the Jamaat’s stance on Kashmir has been influenced by its desire to strengthen its organization and political standing. It has used the Kashmir issue to emphasize its patriotism and loyalty to Pakistan, and the party’s stance on Kashmir has shifted with changes in domestic politics and other factors such as military ties and the role of Kashmiri Jamaat-e-Islami activists. The more the Jamaat’s political fortunes have declined, the more it has sought to use Kashmir to maintain its position.

The Jamaat-i-Islami generally echoed anti-Indian sentiments among Pakistanis, although its focus on India has increased in recent years, particularly since the rise of Hindu nationalism in India and the destruction of the mosque in Ayodhya. The party has opposed talks and normalization of trade and diplomatic relations between India and Pakistan and has also played a significant role in Pakistan’s nuclear program, advocating for its continued development and opposing the signing of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. In Bangladesh, the Jamaat-i-Islami was opposed to the secession of East Pakistan and participated in the military campaign to crush Bengali nationalism. After Bangladesh was created, many Jamaat workers and leaders were executed or imprisoned, while others left for Pakistan. The Jamaat has opposed recognition of Bangladesh and has advocated for Muslim unity over national identities.

GLOBAL ADVOCACY

Mawlana Mawdudi, aimed to be recognized as a Muslim thinker and leader and had close relationships with religious leaders in the Arab world. The Jama’at’s relationship with the rest of the Muslim world is conditioned by the idea that “Islam is in danger”. South Asian Muslims, particularly those affected by the fall of the Muslim state of Hyderabad, are affected by what is called the “Andalus syndrome” or fear of marginalization and disappearance like the Moors in Spain. The Jama’at’s position on events in the Muslim world, such as Kashmir, Bosnia, or India, is also guided by this fear. Some secular parties, such as the Muhajir National Movement, have also used this idea as a political tool.

The Jama‘at’s international relations office has grown in size and prominence and the party has a strong presence in different countries such as Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia. The Jama‘at’s international reach and perspective has allowed it to play an important role in shaping Islamist perspectives on issues of general concern to Muslims. They were involved in the prelude to the Salman Rushdie crisis and have worked with the Islamic Foundation in Leicester, England to secure funding for anti-Rushdie campaigns.

The Jama’at views the PLO as less genuine than Islamist groups like Hamas and Islamic Jihad, but the conflict is not a central concern for the party. In recent years, the Jama’at has felt compelled to defend Islamist ideology in the peace process and has argued that the rejection of an unfair peace process by Islamists is justified. The Jama’at views the future of Jerusalem as an Islamic issue, not just a Palestinian-Israeli one, and fears the possibility of a permanent non-Muslim jurisdiction over the third-holiest city of Islam. The party’s position on the Arab-Israeli conflict will likely impact Pakistan’s relations with Israel. The Jama’at opposed recognition of Israel by the Organization of the Islamic Conference, and the government’s initiative to recognize Israel has been stopped. There is a widely held belief in Pakistan that Israel is behind American pressure to shut down the country’s nuclear program, which the Jama’at supports. The party has cast the nuclear issue as a nationalist-Islamist cause and equates any scaling back with giving in to American pressures.

The Jama’at-i-Islami has been involved in the Islamist movement in Central Asia since 1977 by disseminating its literature and establishing contacts with local Islamic forces in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. It has a strong interest in the region and views it as a continuation of the Afghan jihad. The party has a symbiotic relationship with the Pakistan state, where the state finds the Jama’at’s politics and organizational reach useful to its aims, and the Jama’at subsumes pan-Islamism under national foreign policy. The Jama’at is also motivated by concern over Russian hostility to Islam and views Central Asia as a key battle in a larger anti-Russian war. The Jama’at has recently extended its strategy to include Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, China, where it sponsors 100 Uighur students at the International Islamic University in Islamabad.

The Jamaat-e-Islami has historically held an anti-Western stance, including opposition to the country’s pro-Western foreign policies and membership in Western-led defense alliances. This was largely driven by the party’s belief in a “Third Worldist” stance and closer ties with the Muslim world. However, this stance was not as clear-cut due to Pakistan’s geostrategic needs and its ties with Saudi Arabia and the US during the Cold War. In the late 1980s, the Jamaat-e-Islami became more openly anti-American due to a perceived end to the US-Pakistan strategic consensus and the influence of Pakistani nationalism. The current secretary-general, Sayyid Munawwar Hasan, is even more strident in his opposition to the US. However, anti-Americanism has not always been a central concern for the party and it has balanced criticism with calls for bridge building between Islam and the West. The influence of domestic politics on the party’s attitude toward the US has not been uniform and there have been instances where the Jamaat-e-Islami has been accused of doing the bidding of Washington.

The Jamaat-e-Islami has a complex relationship with international organizations. They have supported organizations such as the OIC that serve the purpose of Islamic unity, but opposed organizations like CENTO and the UN which they view as biased against Muslim interests. In recent years, the Jamaat has become active in its opposition to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and its austerity measures, which it argues harm the poor and are imposed by a Western-controlled international agency. The party has also rejected IMF demands to cut the military budget, claiming it threatens Pakistan’s independence. The Jamaat has found support from Malaysia’s Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed’s recent criticism of Western economic institutions.

The Jama‘at-i Islami’s approach to international relations is shaped by multiple factors including ideology, historical legacy, pragmatic interests, domestic political imperatives, state policies, and events such as the Afghan war. Ideology and idealism provide a vocabulary and perception, but do not completely control the development of the party’s understanding of international relations. It is multi-dimensional and continues to evolve over time in response to both international and domestic events. The development of a systematic approach to foreign policy will be influenced by these factors and their interactions.

The views expressed herein may not necessarily reflect the views of JI FAD and/or any of its affiliates